Then a problem arises; translating that drawing or sketch into a finished work. As almost any artist knows, pencil sketches almost always express a freedom and spontaneity that is very difficult to achieve in finished work. Some artists, like many of the Impressionists, painted with great speed outdoors on the spot so that they could get that spontaneity in the finished work. Some artists, on the other hand, might simply paint directly on the canvas with very little planing, thus doing in the studio what the Impressionist did in the field. But that approach simply is not practical for more "finished" or meticulous kinds of work. Many traditional painters were working on huge canvases with figures (sometimes many figures) in their paintings. Such paintings required detailed and meticulous planning. Think of paintings by Rubens or even John Everett Millias. Paintings by artists like these obviously couldn't be painted without sketches and planning. Benjamin Robert Haydon, one of history's more interesting artists, worked on one of his major works for over six years.

One of the most challenging processes of art in this sense must surely be Comic Book art. Though comic book figures are almost all done by a kind of consistent and reoccurring pattern, I have seen many finished comic books in which the drawings were obviously excellent, demonstrating motion and fluidity, but the inking process has essentially killed this spontaneity and the finished work just doesn't make it. My own father experienced this when he created the Steel Chameleon super hero in a comic book in the 1980s. On the other hand, Comic book art has the advantage in the fact that one can ink directly over the sketch, making the retention of spontaneity achievable. However, much comic book art is fundamentally about motion and movement so the challenge remains high.

I have struggled with this problem myself in different ways and on different occasions. Sometimes, it is quite straightforward, as in the case of this drawing of a Joshua tree which I then turned into a large painting.

|

| And here is the finished Painting |

It still think that the drawing has a graphic charm that is missing in the painting in this case but the painting also has its advantages.

Sometimes the problems are more challenging. Here is a sketch and a painting that I recently completed.

In this case I really liked the drawing but something about the painting just didn't quite work for me.

In the next case I think the painting actually improved on the drawing. I am not sure how that happened, and it seems to be sadly rare.

In very rare cases I have used the simple technique of squaring a drawing off in order to replicate it very accurately on the board on which I am painting. This, technique works better, I think, with something like landscape painting. Here is a sketchbook drawing (which I took from a very small sketch that my father did) which I squared off for painting.

|

| The blue paint smears on this drawing illustrate the chaos of the studio |

Here is one, more extreme, example. In this case the sketch was a very small drawing (about 2x4 inches) with very little detail, which was then worked up to a much larger (24x36 inches) oil painting. In this case I used an middle step which consisted of a coloured drawing of the idea.

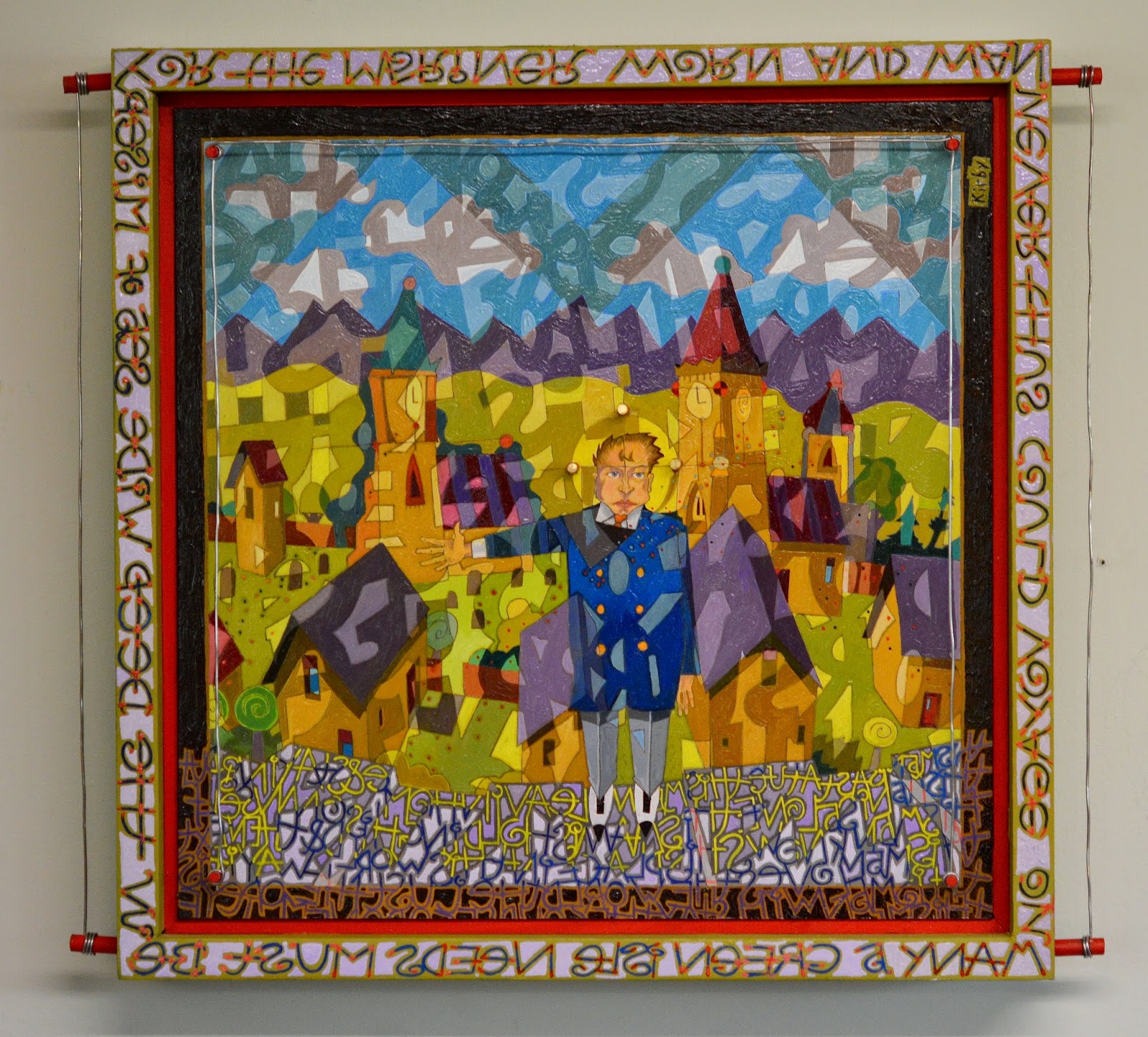

Here is an example of my 3-dimensional work which I just make the barest bones of a sketch idea and the rest is worked out as I build and paint the piece. It is somewhat ironic that these works are actually much more complicated and yet I don't seem to have an inclination to work out the details on paper. Instead, I think about these piece for a lot more time, working out most of the details in my head. Of course work like this is a much bigger commitment and this particular work is over 400 hours in the making.

These are just a few examples of the process from sketch to finished work. I am sure every artist has their own stories of success and failure when it comes to this process. It seems to me, after many years of experience, that every person has their own "natural" sense of colour and style which comes out in their art work without thought or plan. Some artist have a knack for doing very slick, commercially popular work (I don't mean this in a derogatory way) and they have certain advantages when it comes to certain kinds of work. Other artist may have a quirky charm about what they do, which may make commercial success more challenging but can also find a place. But regardless of your natural sense of colour and style, I think this problem of turning a sketch into a finished work is a universal dilemma.